Project

You Have Been Seen

Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 2022

No Tears Left To Cry / You Have Been Seen - Organ Vida exhibition

Curator and author of the text - Jozefina Čurković

Exhibition design - Benussi&theFish

Audio narration (duration aprox. 3 min)

Spatial construction (aprox. 2,5 × 2,5 × 2 m)

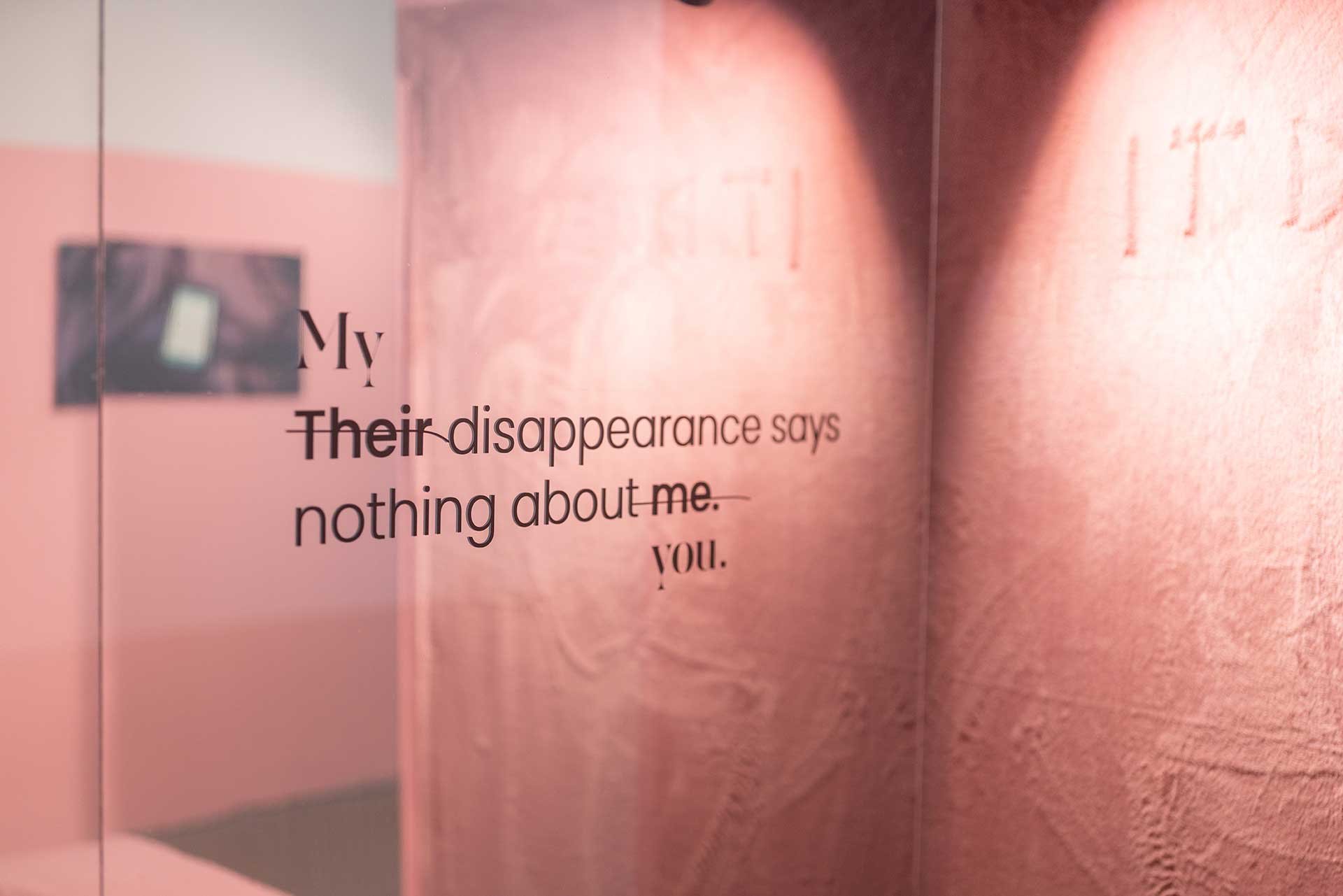

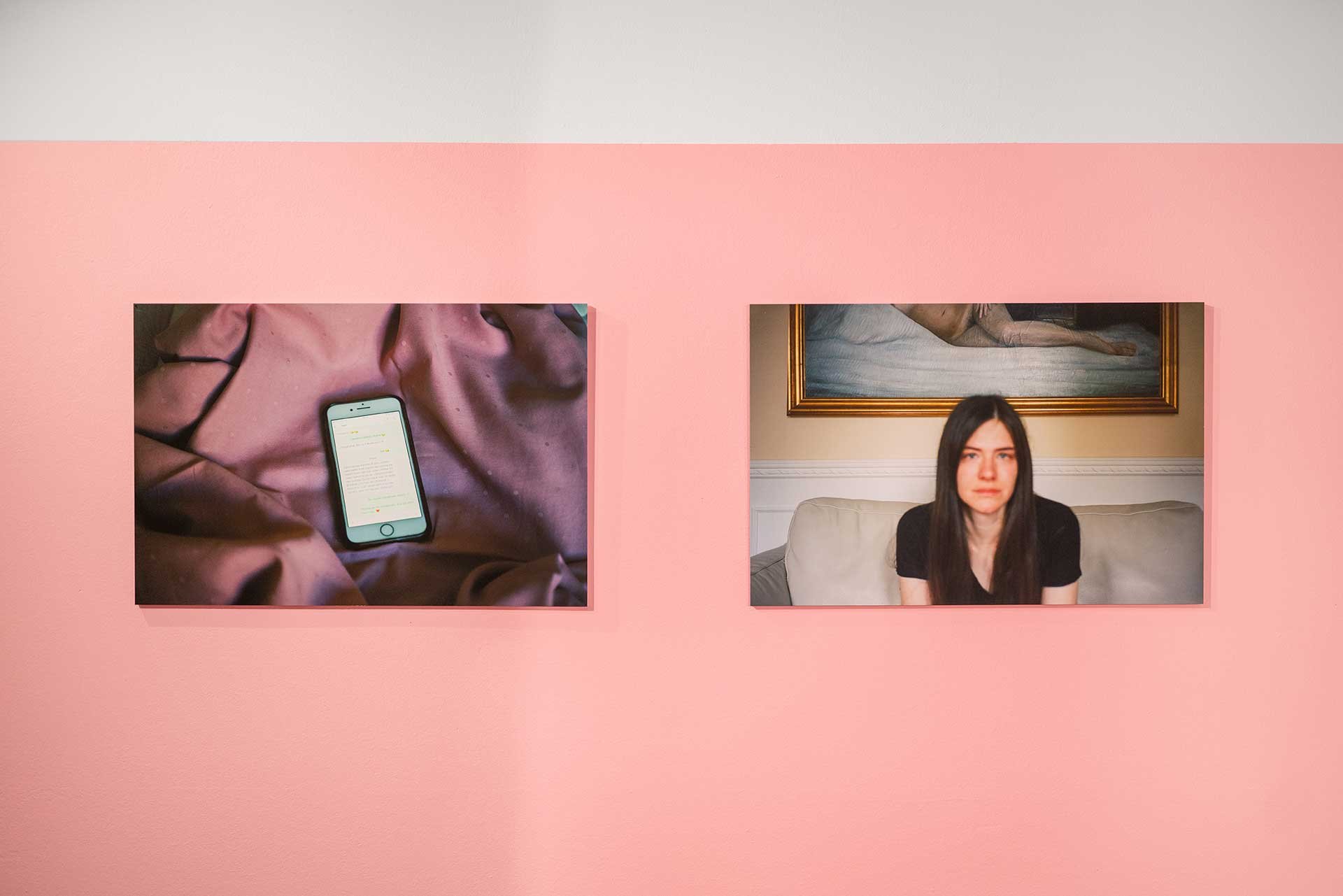

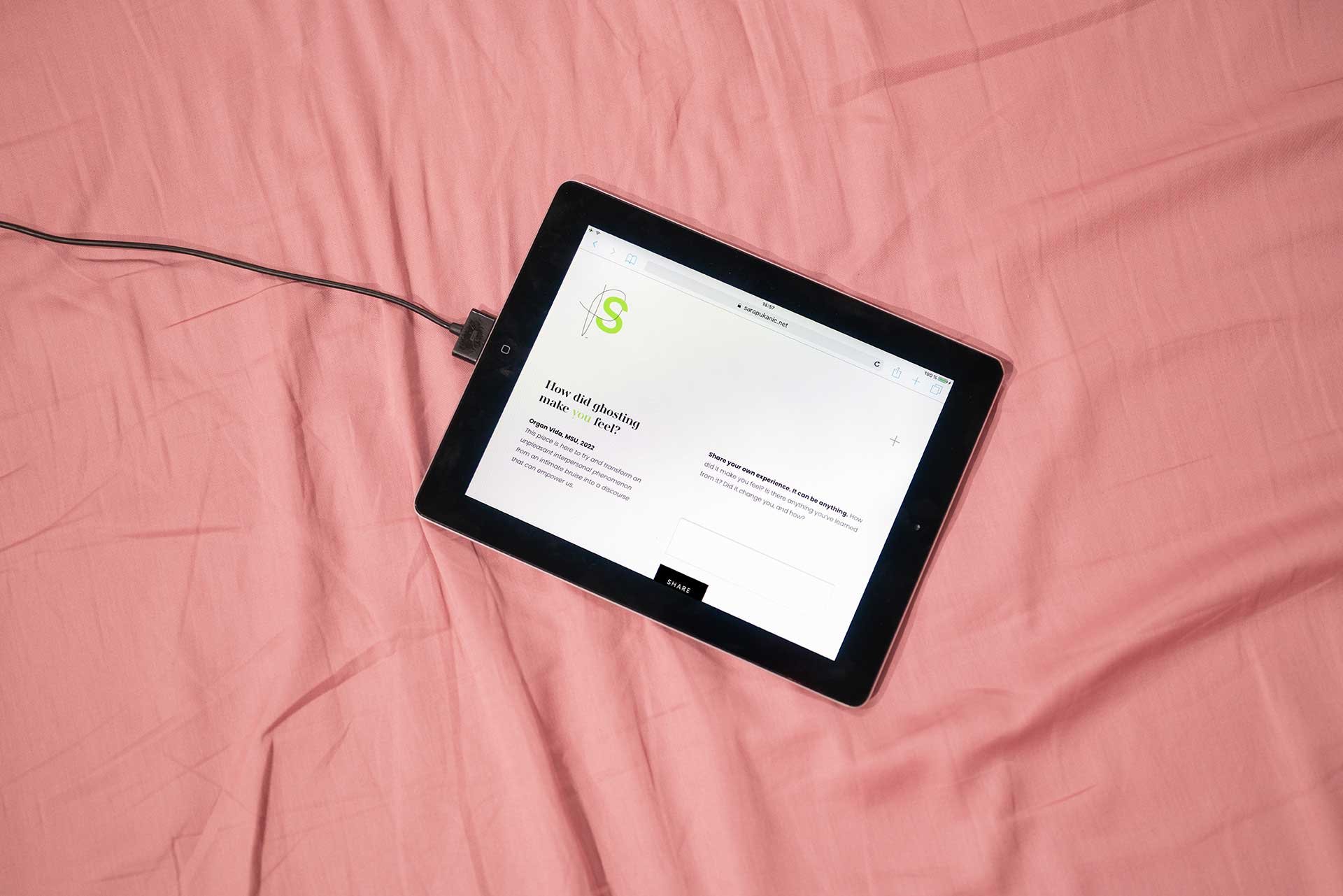

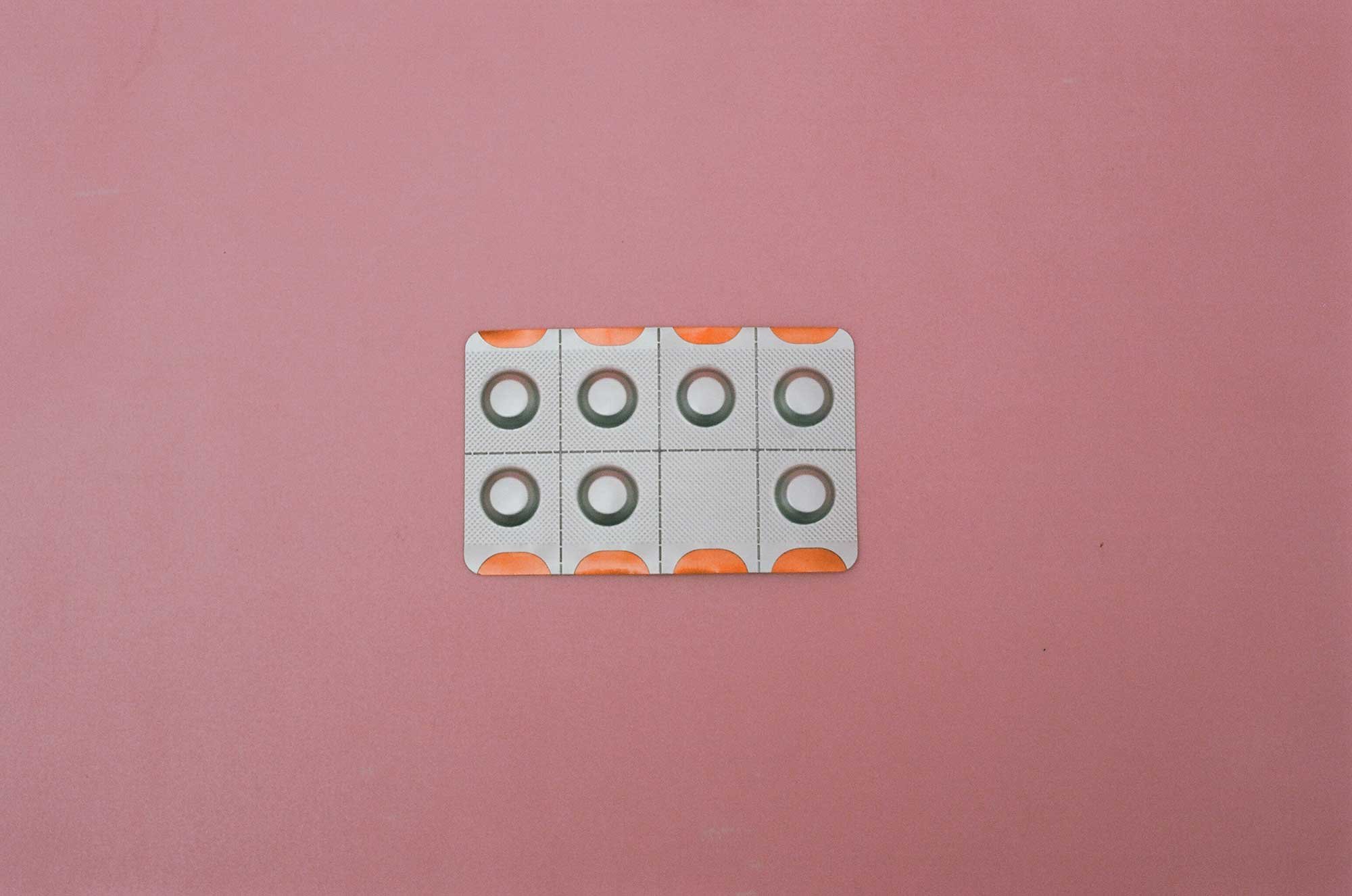

Ghosting is an act of sudden interruption of communication without warning or explaining yourself to another person. Ghosting became an effective strategy in dating today. Many of us experienced it. Whether we are ghosting or we are ghosted, we may end up overwhelmed by confusion, shame and insecurity. During such a period of liminity - in which we come to the realization of what happened and allow anxiety to flood us - Sara Pukanić recorded symbols of her own obsession: objects and places that played a role in the first and only encounter with the person who ghosted her.

By expanding the photograph series, originally post-ghosting photo diary, to the spatial construction, the work of You Have Been Seen draws attention in the way we prosecute feelings that we would rather not share in public. Furthermore, it designs the environment that allows an audience to experience this phenomenon not only through photography, but also through other sensory stimuli. The materials and interactive nature of spatial installation communicate feelings of insecurity, discomfort, exposure and disorientation. Project does not only deal with emotions that come from ghosting, but also with reflections of our destabilized reality. It emphasizes the potential of sharing these feelings to use them for analysis and demistification of the phenomenon in question.

Ghosting is observed not only within the binary opposition a perpetrator (ghoster) vs. victim (ghostee), which assumes the one-way relationship between the subject and the object, active and inactive, but also within the socio-political conditions that facilitate such patterns of opinion and behavior.

-

Ghosting is defined as an act of abruptly cutting off contact with someone without giving that person any warning or explanation for doing so. Even when the person being ghosted reaches out, they’re met with silence. Many of us have experienced it, however, unlike fictional characters we read about or watched encounter it, a grand, transformative epiphany following such experience may have eluded us. Whether a ghoster or ghostee, it's possible that, overwhelmed with confusion, shame and insecurity, we turned to questioning the initial settings of that particular relationship and all potentialy incriminating things we did or said.

By embedding a series of photographs, originally post-ghosting photo-diary, into spatial construction, You Have Been Seen draws attention to the way we process the feelings we'd rather not share in public. During a short but slow period of liminality – in which one comes to realize what happened and allows for anxiety to wash over them – the author captured some tokens of her obsession: objects and places which played a part in the first and only encounter with a person she was ghosted by. Each photograph can be interpreted as one of the stages in the process of self-healing.

The exhibition design is based on photography lending itself to a more ambiental piece, aiming to supply the visitor with a multi-sensory experience. Upon entering the space, visitors interacts with its' components: observes the photographs, adjusting his points of view to the asymetrical layout; touches the surfaces; rests on a tabouret; listens to the author's narration of her experience via headphones and enters their own experience or response in a digital repository. The materials used communicate feelings of insecurity, discomfort, exposure and disorientation.

The work tackles not only emotions that arise from ghosting as a strategy of ending a relationship, but also the reflections of our destabilized reality. It emphasizes the potential of sharing these feelings amnogst us in order to analyze and demistify the phenomenon in question. Ghosting is observed not only within the binary opposition of the perpetrator (ghoster) – the victim (ghostee), which presumes a one-way relation of subject and object, active and inactive, but within the socio-political conditions that enable and facilitate such patterns of thought and behaviour, namely the disintegration of the idea of wellfare. At the level of affect, this failure lead to a steady decline in empathy. At the same time, the economy of happiness ruthlessly imposes upon us exponential growth and development, awareness and uncompromising self-love. It is this obsession with the individual that privatizes our emotions, which can easily lead to depreciation of the effect that social structures have on the behavior of the individual as well as collective well-being.

References:

Ahmed, Sara, 2020. Kulturna politika emocija, Fraktura.

Grdešić, Maša, 2020, Zamke pristojnosti: eseji o feminizmu i popularnoj kulturi, Fraktura.

hooks, bell, 2001. All about love: New visions. Harper Perennial.

LeFebvre, L. E. et al. 2019. “Ghosting in emerging adults’ romantic relationships: The digital dissolution disappearance strategy”. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 39(2), 125-150

Project

Katarina

(Croatian: Katarina), 2021

I believe in the idea of a soulmate.

I believe in the idea of a soulmate and that is exactly how I would describe my relationship with Katarina. She's my best friend for 22 years. Whenever they asked us as children for how long we know each other, I would always add years for it to sound better.

Now I don't have to do it anymore. I'm proud of us. There is no other relationship I have been intently building for so long. I see the magic in being able to continue building it and knowing we have our lives ahead of us.

My way of expressing gratitude for this relationship was turning it into a series of my friend’s portraits. These photographs are a statement of my recognition, and at the same time a document of a very ordinary afternoon.

Project

They and I

(Croatian: Oni i ja), 2021

This series came to be as a result of a kind of personal archeology.

In an effort to explore my relationship with my late parents and resolve the feeling of incompleteness, I delved into family albums and decided to recreate several archival photographs of my mother, taken by my father. Posing as my mother once did and putting on similar clothes, I acted both as a photographer and a protagonist of photographs, putting myself in both of theirs’ shoes.

By doing this, I commenced a kind of trans-temporal dialogue with them. I exposed myself to the unrelenting eye of the camera, letting go of precision and control I normally employ. Matching original photographs to the reinterpretations and setting them up as a continuous sequence makes it harder to discern my mother’s image from my own, my father’s framing from mine.

This kaleidoscopic overlap enables me to symbolically pick up where we left off, reconcile and experience the desired catharsis.

Project Pink

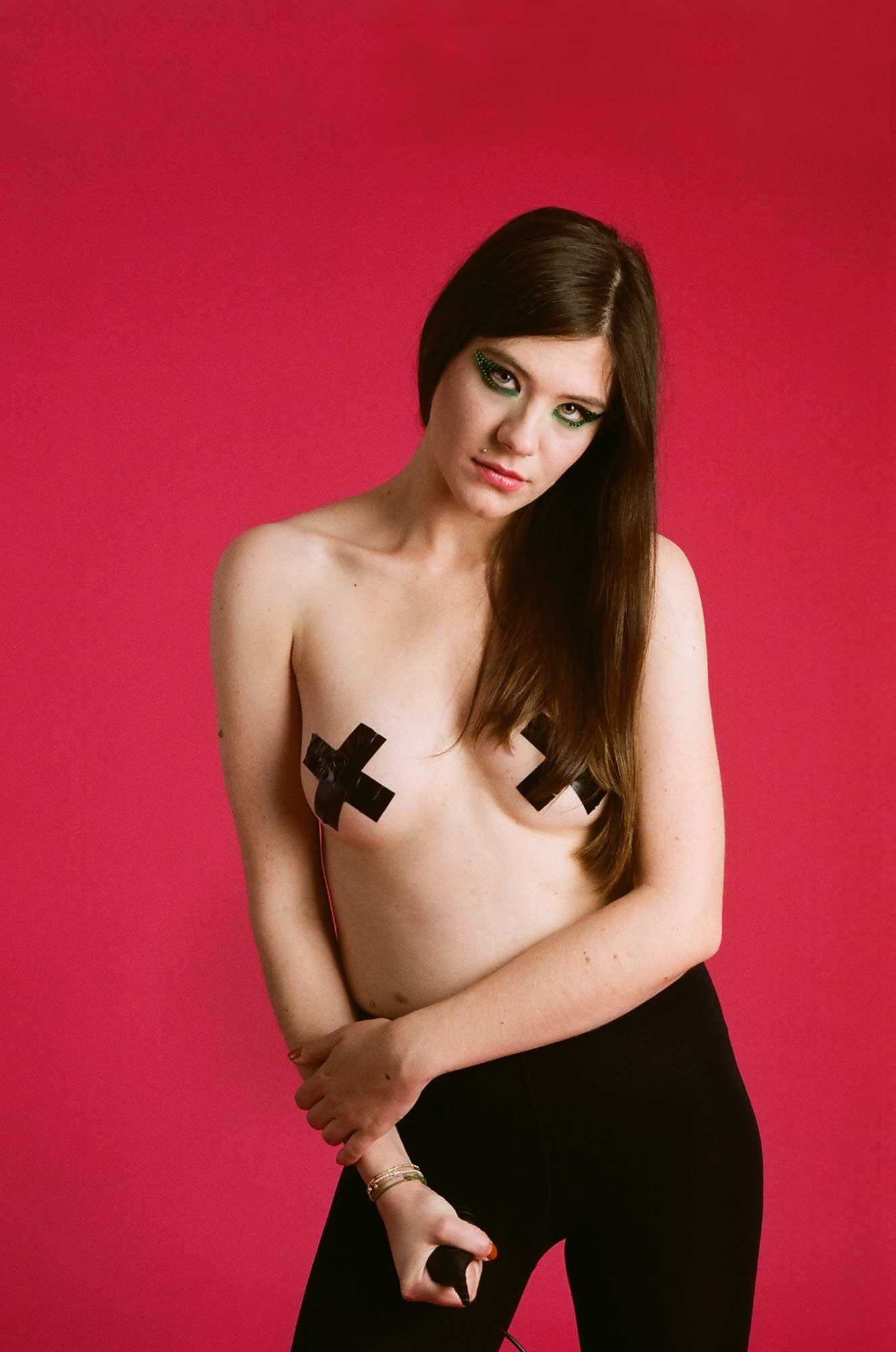

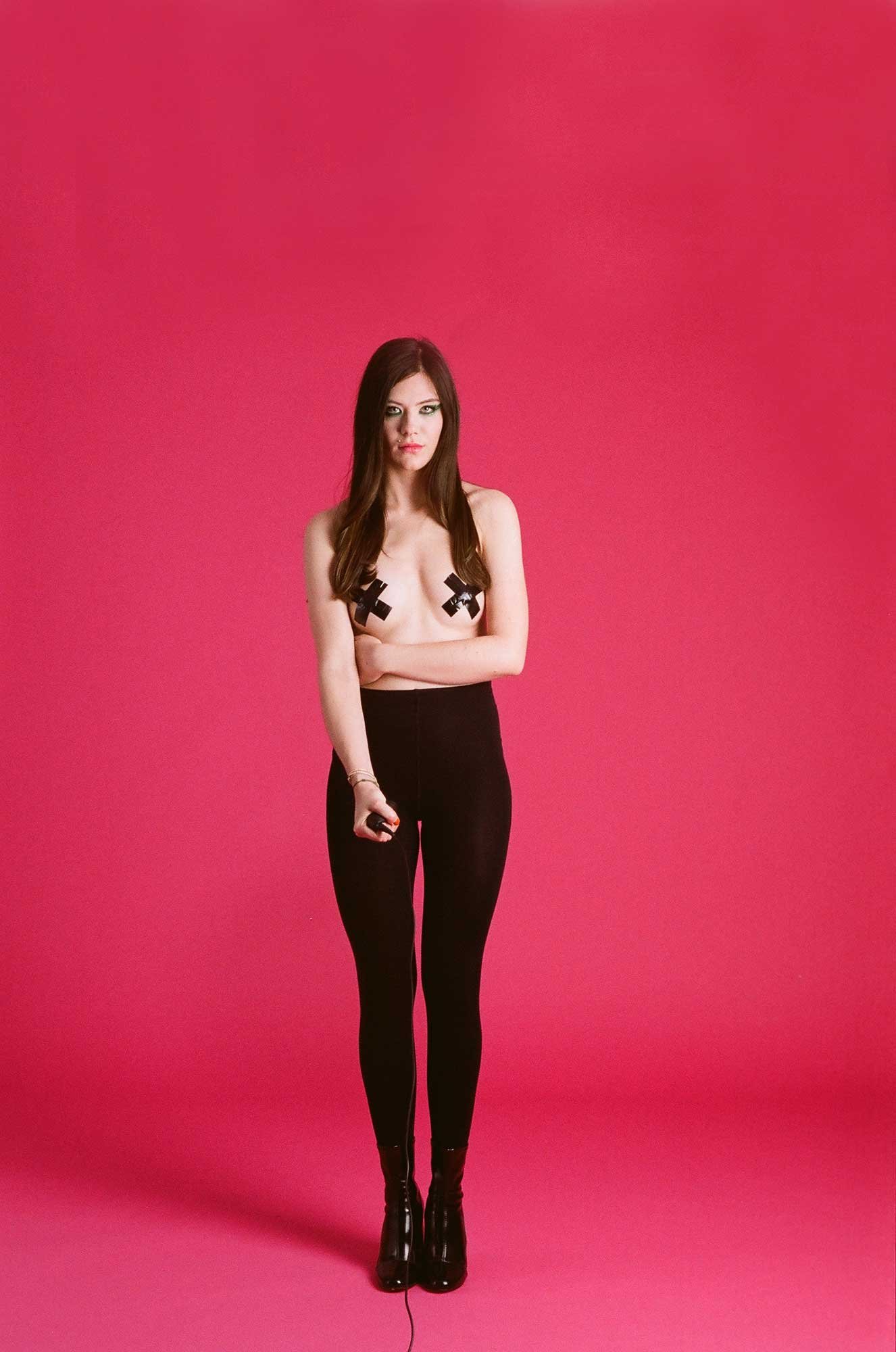

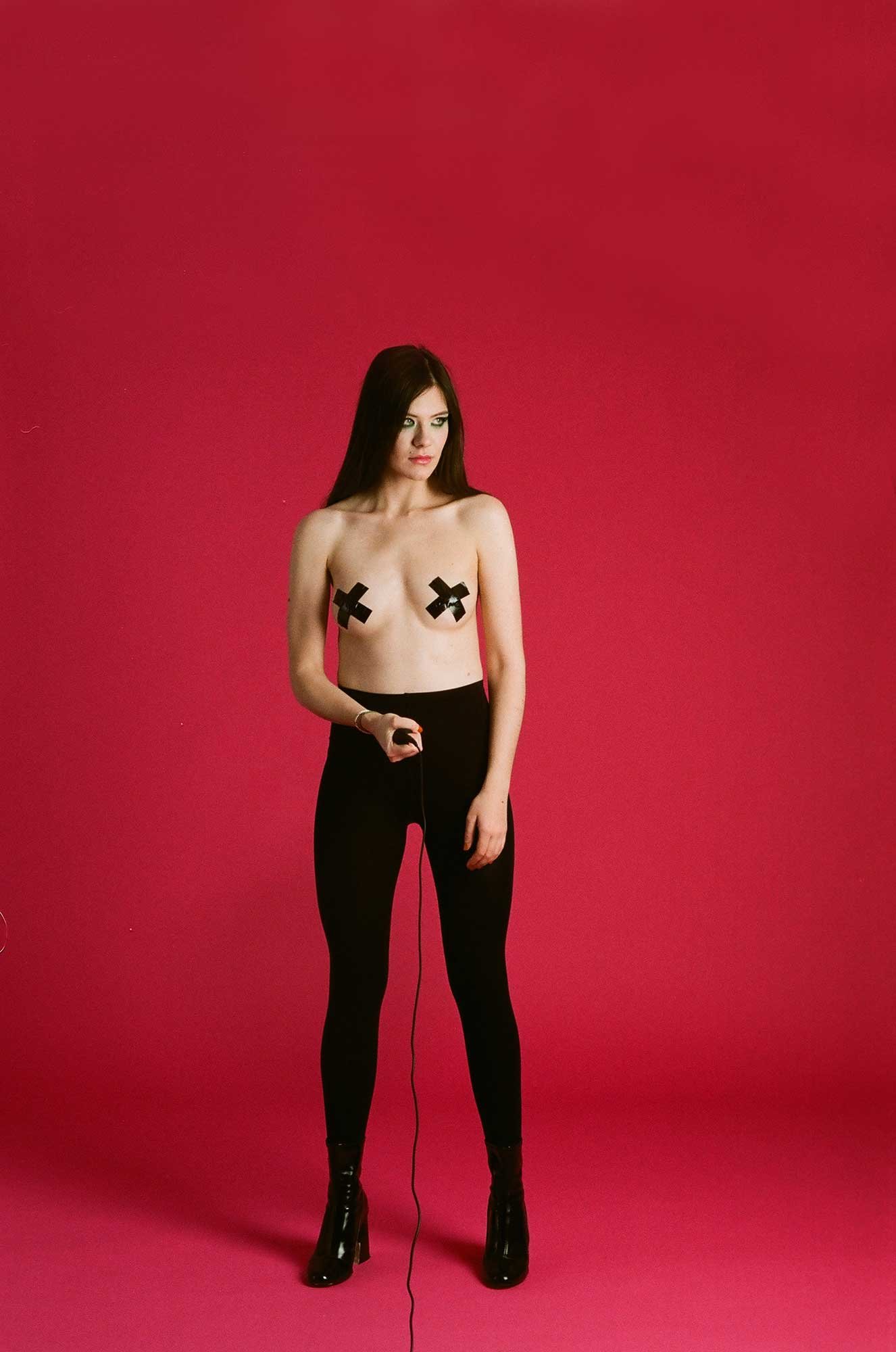

(Croatian: Roza), 2020

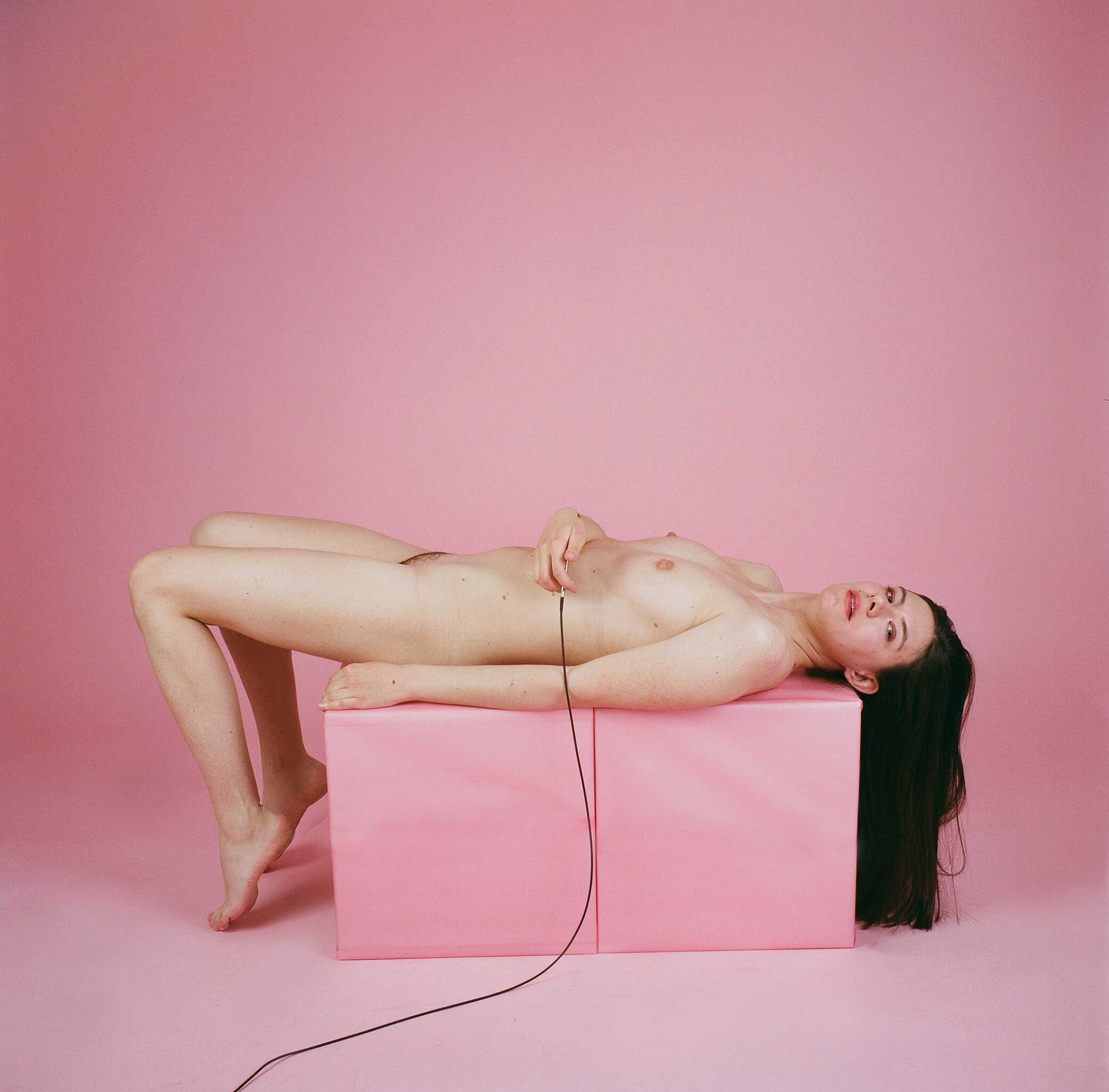

Pink emanates notions of care, tenderness, confidence and acceptance.

For me, pink is the color of universal love. It’s my favorite color. The series Pink consists od images of Barbie dolls, my mom and dad, flowers, shrimp, my phone, my bed, toothbrushes and floss, as well as self-portraits. Old Barbie dolls are a symbol of me always getting what I wanted as a child.

I like thinking of mom and dad all wrapped in pink; I think about them every day. Whenever my mom cooked shrimps, I knew it was a special day: everyone in the house was happy. Throughout my childhood, I had little to no control of certain situations, so now I’m taking control of the little things, such as frequent brushing and flossing my teeth. My phone is always with me, I don’t like being alone with my thoughts. My big, round bed provides me with a sense of tranquility and comfort. Flowers help in treating mood disorders, as they reduce anxiety and restlessness.

As I capture myself nude for the first time, I wonder how I will feel in front of a pink background, entering my personal sanctuary of pink.

Project

One for my soul

(Croatian: Jedna za dušu), 2019

I believe he didn’t want to break the spell of an unwavering, adventure-seeking boy he was.

In the winter of 2019, I decided to make a series of portraits of my uncle Boris. Boris had been an oncology patient for seven years at the time. Starting the project, I had no way of knowing he would pass away eight months later. My desire was to get closer to him and explore the places where he loved spending time, learning more about him as a result.

Each time we met, he was full of vigor, ready for a new adventure, dressed in one of his fishing or cowboy outfits. Our encounters were bursting with positivity and laughter, so much so that at times I forgot how ill he actually was. He loved fishing, he loved horses, he loved the nature. I suppose nature distracted his thoughts from pain. For that reason, the majority of portraits was taken in such surroundings. I felt as if taking a photo of him could, somehow, prolong his life for just a bit. The last time I had a chance to photograph him was for his birthday, in May 2020.

After that, he felt worse and it started to show on his face; he refused to be photographed. I believe he didn’t want to break the spell of an unwavering, adventure-seeking boy he was.